PUT ONLINE 29.4.2024

Robert Charroux

Trésors du Monde, Trésors de France, Trésors de Paris

enterrés, emmurés, engloutis

Editions Fayard, Paris, 1972

(Trésors du Monde, 1962, Revised Edition)

FRENCH ORIGINAL

Chapter XIX

The Treasure of Rennes-le-Château: 8 billion francs in a grave

75 treasures at Charroux Abbey

There’s a definite historical basis to the treasure of Rennes-le-Château, a tiny French village in the Corbières hills 60 kilometres south of Carcassonne.

Its church and its several houses are perched on a rocky peak reached by a steeply sloping and bumpy five-kilometre road.

It would need something bordering on a miracle for a treasure to be hidden in this Sleepy Hollow where the cars slide all over the place and can just about pass each other.

But there really is a treasure in Rennes-le-Château. We know it’s real because it was found half a century ago by the local priest, Bérenger Saunière, who, after dipping into it (although only slightly no doubt) bequeathed it to his housekeeper and mistress, the pretty Marie Denarnaud, who bequeathed it in her turn to Monsieur Noël Corbu.

But Marie Denarnaud’s legacy was incomplete, because she died before she had a chance to reveal the treasure’s whereabouts.

Since then Monsieur Corbu has been prospecting, digging and probing in the hope of unearthing the gold and silver coins, jewels and precious stones of a treasure valued at 8 billion francs, and which serious historians think is the French royal treasure of the 13th century.

‘Once upon a time,’ says Noël Corbu, ‘Rennes-le-Château was a town of 3000 souls and a circle of ramparts of which we can still see the ruins.

‘When I was searching for the treasure I found some ancient coins, some pottery, weapons and the skeletons which I’ve filled my little museum with.

‘According to the historians of Carcassonne the origins of the treasure go back to February 1250. That was when the revolt of the Pastoureaux, which had kicked off in Northern France under the leadership of the mysterious ‘Master of Hungary’, reached its peak and the wave of serfs and beggars swept into the Midi.

‘Blanche of Castille, Regent of France, came to Rennes-le-Château – which was then called Rhedae – to find a safe haven in the well-fortified citadel for the French royal treasure which was under simultaneous threat from the Pastoureaux and the muted cabals of the nobility. You should note in passing that the citadel of Rhedae was considered impregnable and was located on the road to Spain where Blanche de Castille knew that she would be able to take refuge in the event of danger.

‘She hid the treasure in the underground chamber in the keep. At least, that’s what some people think.

‘Certainly it’s hard to explain why the treasure has remained intact for so long, especially during 1251 when St. Louis would have been in such great need of financial subsidies which his mother would not have been able to send him.’

In a nutshell, Monsieur Corbu thinks that the treasure formed a sort of reserve which could only be drawn on in situations of extreme urgency and danger.

Blanche de Castille died in 1252 after revealing the secret of the treasure to St. Louis who in his turn confided it to his son Philip the Bold.

Philip died in Perpignan without having had the opportunity to tell Philip the Fair the secret of Rhedae.

In 1645 Rhedae was rebuilt and became Rennes-le-Château. The former fortress was rebuilt a short distance from its original location and is on the site of Monsieur Corbu’s present property.

It’s at this point that the story of the ‘treasure lost and found’ really begins.

It was first found in the 17th century by a shepherd called Ignace Paris who, having lost one of his sheep, heard it crying from the depths of a crevasse. He went down to investigate.

The sheep, frightened by the shepherd’s sudden descent, fled through a tunnel.

Still in pursuit, Ignace Paris emerged into a crypt ‘filled with skeletons and coffins’: the first was terrifying but the second, in contrast, was full of goodies.

He filled his pockets with gold coins, fled in terror, and went home.

His sudden wealth was soon the talk of the village, but Ignace was foolish enough to refuse to reveal where he got it from. Accused of theft, he was killed without having had the opportunity to reveal the secret of the crypt.

Did a rock-fall occur at the entrance to the underground passage? We don’t know, but until 1892 there was no further talk of the treasure, the location of which the descendants of Ignace Paris were destined never to discover.

A chance event in that year brought the local priest, Bérenger Saunière, into the story.

Saunière had become curé of Rennes-le-Château in 1885 and was immediately taken up by the Denarnaud family whose daughter Marie was 18 years old at that time and was working as a hat-maker in the village of Espéraza.

The Denarnaud family, who lodged near the presbytery, wasted no time in moving in there.

In 1892 Saunière was obviously held in high esteem by his parishioners, both for his zeal and for his good nature.

It was in that year that he secured a municipal loan of 2400 francs to restore the Visigothic main-altar and the church-roof.

The mason Babon from Couiza set to work and, one morning around 9 o’clock, called the curé over to show him, in one of the altar-pillars, four or five wooden rolls, which were hollow and sealed with wax.

‘I don’t what these are’, said Babon.

The curé opened one of the rolls and, we think, extracted a parchment manuscript written in a mixture of Old French and Latin which, at first glance, seemed to contain some passages from the Gospels.

‘Bah!’ said Saunière to the mason, ‘these are just old bits of paper from the time of the Revolution. They’re not worth anything!’

At noon Babon went to have lunch at the inn, but he was so excited about what had just happened that he shared the news with his companions. Then the Mayor turned up seeking information. The curé showed him a parchment which the Mayor could make neither head nor tail of and the matter rested there.

But not entirely... Saunière decided on his own authority to halt the work on the church.

According to Monsieur Corbu, this is what happened next:

‘The curé tried deciphering the documents. He recognised the verses from the Gospel and the signature of Blanche of Castille with her royal seal, but the rest remained a puzzle. So he went to Paris in February 1892 to consult some linguists, but out of caution only gave them some fragments of the documents to look at.

‘I can’t reveal the sources of my information but I can assure you that we are dealing here with the treasure of the Crown of France: 18 million francs in the form of 500,000 gold coins, jewellery, sacred objects etc.

‘Saunière returned to Rennes-le-Château without knowing exactly what the treasure was all about, but also with some very valuable information that was enough to go on.

‘He searched in the church. Nothing!

‘Marie, for her part, was intrigued by an old flagstone in the cemetery which bore a bizarre inscription: it was the tombstone of Comtesse Hautpoul-Blanchefort. Could the treasure be under that perhaps?

‘The curé locked the cemetery-gate and, with Marie’s help, spent several days on a mysterious task. One evening they were finally rewarded for their efforts and finished by completing the puzzle for which the inscriptions on the gravestone had provided the first clues.

‘From that moment on the relationship between Marie and the curé changed: now she became his confidante and his collaborator.

‘I believe that there are six entrances leading to the treasure, including one in the keep which had already fallen down in 1892.

‘On one of the parchments there are lines counted in toises [Translator: an historical measure, about 6 feet] which lead from the main-altar. Marie and the curé measured this out with pieces of string and found a terminal-point at a place they call the ‘château’, which is waste-ground now. They dug there and found the underground passage and the treasure-crypt where the shepherd Paris ended up in days gone by.

‘The gold coins, the jewellers, the precious vessels were all there, covered in a thick layer of dust, but intact.

‘They decided on a plan. The curé would go to Spain, Belgium, Switzerland and Germany to exchange the coins and then send the money by post to Couiza addressed to Marie Denarnaud.

‘That was what they did – despite the risk and inconvenience – to repatriate the funds.

‘Whatever the case, by 1893 Saunière was a rich man, a very rich man... so rich in fact that he paid for all the repairs to the church-roof and indeed the church itself which he decorated in sumptuous fashion.

‘He restored the presbytery, built the perimeter-wall and constructed a summer-house in a magnificent garden full of rockeries and fountains.

‘He also bought beautiful furniture, and expensive dresses for Marie. He ordered rum from Jamaica and monkeys from Africa, he fattened up the geese in the poultry-yard with biscuits fed to them by spoon – that improves the quality of the meat apparently – and bred show-dogs.

‘In a word, it was life in the grand manner at Rennes-le-Château where Saunière kept open table – and what a table it was! – for all the local gentry.

‘The curé bought land and houses, but always in the name of Marie Denarnaud, and the pretty brunette with malicious eyes and a slender figure became a true châtelaine.

‘Once, when Saunière was travelling, he wrote to Marie:

‘My little Marinette, how are our animals? Stroke Faust and Pomponnet [the dogs] for me, and I hope the rabbits are all right. Farewell for now Marie, Your Bérenger...’

‘To tell the truth there were other beautiful women sharing Saunière’s affections. The names of Emma Calvet, the beautiful Comtesse de B. and many others have been mentioned!

‘This sudden access of wealth affected Saunière’s mind and plunged him into megalomania. He even dreamed of building a château! Prudent in spite of everything however he went to some pains to eradicate the clues that had led him to the crypt. In the cemetery he scratched out the inscriptions on the tombstone of the Comtesse and put the parchments in the treasury.

‘The Mayor came to tell him off about the damage he had done to the tomb and to ask about the wealth that he had access to, but the curé laughed at his concerns, told him about an inheritance from an uncle in America and gave him 5000 gold francs.

‘The Mayor often returned to the fray – and the price was the same every time!

‘Monsignor Billard, Bishop of Carcassonne, was also concerned about the behaviour of his priest but there again, thanks to the money, some good wines and some good cheer the problems were smoothed out.

‘In 1897 Saunière started building-work on the Villa Béthania which, with the ramparts and the tower, would cost a trifling million gold francs. To ensure that he had flowers all the year round he had a glasshouse constructed on the rampart-walk.

‘Monsignor Billard’s successor, Monsignor de Beauséjour, then came along and acted the spoilsport. He demanded explanations from Saunière, summoned him before the Roman Curia and finally banned him from saying Mass.

‘A new priest was then appointed to Rennes-le-Château. Saunière had no parish, but in the chapel at the Villa he continued saying Mass with almost the whole village attending. The new priest, disheartened, resigned and no longer had to travel the bumpy road from Couiza to Rennes-le-Château.

‘Saunière also planned a new development programme: he wanted to raise the Tower a bit, build a proper road to Couiza, buy a car, and put the whole village on mains-water. His bills rose to 8 million gold francs (in 1914) or about 8 billion new francs. This money Saunière held in cash.

‘On 5 January 1917 he signed some order-forms for the project but cirrhosis of the liver finished him off on the 22 before he was able to realise it.

‘Marie, desolate, put the dead priest out on the terrace seated in an armchair and covered him with a coverlet decorated with red tassels. All the villagers came to pray and take away a tassel each as a relic of the sainted man.

‘Marie Denarnaud was now sole proprietor of Rennes-le-Château, for everything had been put in her name, but she ended her days almost cloistered, refusing visitors. It’s possible also that she never went back to the treasure-crypt.

Now we come to Noël Corbu, the third character in the story and Marie Denarnaud’s heir.

Monsieur Corbu knew Marie at the end of her life, from 1946-53, and met her quite by chance.

With his wife he lodged with her and managed to win her confidence and friendship.

‘Don’t worry, Monsieur Corbu,’ she said to him one day. ‘You’ll have more money than you’ll ever be able to spend!’

‘But where will you get it from?’ asked Noël.

‘Ah, I’ll tell you that when I’m ready to die!’

On 18 January 1953 she fell sick, lost consciousness and died, taking her secret with her to the grave.

So once again the treasure of Blanche of Castille was lost, and this time lost for good it seems!

But in fact there’s no evidence that the treasure was the treasure of the mother of St. Louis. Some say that it was actually the treasure of Alaric whose capital was Rennes-le-Château. Others – and this seems more likely – incline towards it being the treasure of the Cathars, taking into account that Rennes-le-Château was their second citadel after Montségur.

Some recently discovered documents shed new light on the mystery. It seems there could have been several treasures, and that one of them could be that of the Templars!

THE MYSTERIOUS FLAGSTONE

If we are to find once more the treasure that Saunière found then we have to understand the text engraved on the tombstone of ‘Marie de Nigri d’Ablès, the Lady of Blanchefort, Lady-Seigneur of the parish, who died on 17 January 1781 aged 61.’

She was the mother of the noble Marie d’Hautpoul-Blanchefort who on 26 September 1752 married her cousin, Messire Joseph d’Hautpoul, Knight and Marquis.

This tombstone is in the former ossuary of the cemetery, but Saunière carefully scratched out the inscription on it.

‘How sad that a cultured man like you did not take the precaution of copying the inscription,’ said the historian Ernest Cros one day!

The curé replied that the flagstone was suitable for his project of rebuilding the ossuary and that there was therefore no reason to preserve it, but he was of course dodging the point of the question.

It was again Ernest Cros who pointed out that the author of the funerary inscription was either a member of the d’Hautpoul family or Abbé Antoine Bigou, curé of Rennes-le-Château from 1774 to 1790 and deported under the Law of 26 August 1792.

He died in exile, probably in Sabadelle, on 21 March 1794.

Before he left Rennes-le-Château he finished, in the church, the installation of a crypt begun by the family of Voisins, part of which was in the belfry and part under the flagstone floor of the church.

In 1891 Saunière discovered where the treasure was hidden and removed it.

This fact is proved by the generosity he showed to his colleagues in the vicinity.

To abbé Grassaud, curé of Caudiès-de-Fenouillèdes, he presented a beautiful chalice and settled the bills of its suppliers with jewellery of ancient design.

When Saunière was asked about the treasure he used to reply:

‘They say I found a treasure! Me l’an donat ley panat, ley trapat, en tot cas bas teni! [Provençal:

‘They gave it to me, I stole it, I seized it, and whatever happens I’m keeping it!’]

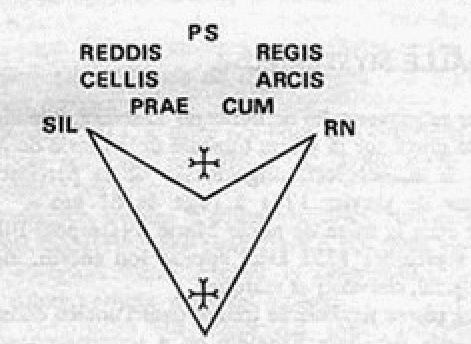

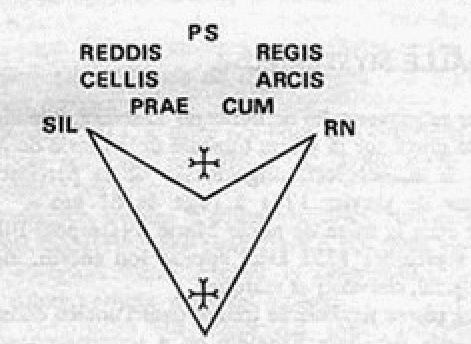

Here, partially reconstituted by Ernest Cros following statements by the residents of Rennes-le-Château, are the text and drawing of the rebus which provided one of the two keys to the enigma:

Interpretation:

PS: pars [part]

REDDIS: to Rennes

REGIS: of the King

CELLIS: in the cellars

ARCIS: of the citadel (another interpretation possible)

PRAE-CUM: of the Heralds (abbreviation of praeconum, the heralds of Christ, one of the designations of the Templars in the 13th and 14th centuries.)

So we have: ‘At Rennes a treasure is hidden in the cellars of the citadel of the King. This treasure belonged to the Templars.’

Alternative interpretation:

PS: property

Regis: of the King

Reddis: at Rennes

Arcis: de Blanchefort (blanca fortax, arcis) [Translator: The only Latin word fortax I know of means the ‘base on which a furnace rests’.

Cellis: in the cellars/caves (or crypts)

Praecum: coming from the Templars.

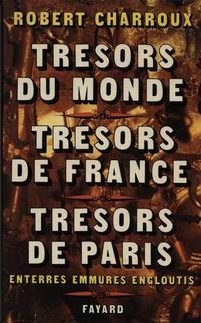

THE STONE OF COUMESOURDE

According to a stubborn tradition (and perhaps one without a factual foundation) the tombstone can only provide the first key to solving the puzzle of the treasure.

The second key was carved on the flagstone of Coumesourde which Ernest Cros discovered in 1928 near Rennes-le-Château towards the summit of mark 532 on the carte de l’état-major.

Since the 13th century the families of Voisins, Marquesave, d’Hautpoul and Fleury have held, through unbroken inheritance, the secret of the location of one or more treasure-hoards formed during the troubles associated with the French Revolution.

A chronicle tells us that in 1789, before emigrating, the counts of Fleury carved ‘enigmatic clues to the secret on the tombstone of the Lady of Blanchefort and also on the stone of Coumesourde.’

One of the treasures reverted to the King by right (cf. the affair of the Infants of Castille, the grandsons of St. Louis.)

Another came from the Templars (cf. the affair of the great families of Roussillon belonging to the Majorcan party) and the nobles we mentioned above have regarded them as their property since the disappearance of the Templar order.

This treasure, divided into two lots, was buried or walled in during the 14th century on the lands of these families:

- In Le Bézu, north-east of Rennes-le-Château.

- In Le Val-Dieu, south-east of Rennes-le-Château, at Le Casteillas or in the Stream of Couleurs.

The stone of Coumesourde was hidden in a crevice in the rock and its whereabouts indicated very discreetly by an arrow and a cross-patty carved into the rock in intaglio. [Footnote: As it was for the treasure of the Carthusians of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon]

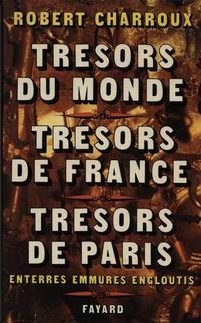

Here is the legend and its interpretation by Ernest Cros, taking into account some effaced or illegible words:

SAE: la Sauzée (Sauzils)

SIS: les Roches

✠ : Cross-patty of the Templars

IN MEDIO LI LINEA [line in the middle?] : the bisector of the angle SAE -✠ - SIS

UBI M SECAT [where M cuts] : the point where it intersects the longest side of the triangle

LINEA PARVA [= short line] (understood: UBI M SECAT): the point where the shortest side intersects the longest side

PS PRAECUM: part of the treasure of the Templars

✠ : Cross-patty of the Templars, indicates Les Tiplies or the Roc du Bézu where this carved cross was still visible in December 1958 (the same sign was also to be seen in 1958 on a rock in Le Val-Dieu.)

We could therefore theoretically locate the treasure by constructing on a carte d’état-major the geometrical figures indicated by Ernest Cros.

The inscription could have been traced by a member of the d’Hautpoul-Fleury family before emigration.

But two major difficulties present themselves:

the text of the flagstone of the Comtesse de Blanchefort, irreparably destroyed, was only reconstructed from memory.

- what we actually have of the text from Coumesourde has whole words missing, and the position of the carved characters (extremely important!) is very approximate.

The task facing the treasure-hunters is therefore to recover the whole text.

Ernest Cros who was a Johannite disciple (an Oriental Christian sect approved by the Grand Bailiffs of the Temple) had the Stone of Coumesourde brought to Paris either for his family to look after or, more probably it is thought, to the headquarters of a secret society.

Since that time (1945-1946) the stone has disappeared.

If some disinterested person was able or willing to provide some clues on the exact text and the layout of the carved words then the treasure of the Templars could perhaps deliver up their gold coins and their priceless documents!

These lines could perhaps be read by the current owner of the stone.

THE INCREDIBLE PIERRE ALQUIER!

In 1960 Monsieur Charles Abbot, a former police officer, who was lodging with Madame L. at 225 rue de Charenton, Paris, made some interesting disclosures to us.

‘During the 1914-18 war,’ said Monsieur Abbot, ‘I was convalescing at the hospital in Choisy. My neighbour in the ward was a mason from Espéraza (Aude).

‘The days were long and we chatted as much as we could to pass the time.

‘That was how the mason, whose name I’ve forgotten, came to tell me about the treasure of the abbé Saunière.

‘He told me that in 1917, fearing the arrival of the Germans, the curé filled in the ossuary which in those days was located immediately on the right-hand side when one entered the cemetery.

‘In fact it wasn’t an ossuary in the true sense but a brickwork holding-trench where, no doubt, coffins were placed when they were awaiting burial.

‘Anyway, at the bottom of this trench my neighbour told me that he had seen, much to his astonishment, a small door or hatch leading to he doesn’t know where.

‘Having thought a lot about it he now thought that this had something to do with the treasure that people were always talking about in Espéraza and Rennes-le-Château.’

Another witness, but a rather suspect one, is Monsieur Pierre Alquier of Perpignan, who was a porter in the market in the Place de la République with whom we were in correspondence in 1959 through the mediation of Madame Marie-Thérèse Rivallier, of 23 Rue Duchalmeau, for our informant could neither read nor write.

He was originally from Espéraza and did manual labour in his youth which suggests that his story is perhaps true.

‘I don’t remember precisely when it was, but it was in May,’ says Pierre Alquier, ‘perhaps it was in 1916, for I was still just a kid, when the curé Bérenger Saunière asked me to go up to the parish to work on something confidential.

‘It was really strange, because I lived in Espéraza, and in Rennes-le-Château and Couiza there must have been labourers older and better qualified than I was, but it’s true that labourers were hard to come by, given that all the strong guys were away fighting in the war.

‘Between the château [Footnote: Pierre Alquier does not mean by this word the ‘real’ château of Rennes belonging to Monsieur Fatin, but the home of the cure which for him must have been sumptuous and lordly. What he actually said was, ‘between the church and the curé’s château’] and the church the cure asked me to dig a hole about 6 to 8 metres deep. We found, protected by an iron grille all covered in rust, a subterranean passage which ran alongside the church. With my pickaxe I made the lock spring.

‘After that there was a tunnel about 3 metres long and then we entered a crypt filled with treasure, weapons and skeletons.

‘I didn’t touch a thing, because the curé didn’t want me to.

‘He told me to leave and gave me 6000 silver francs for my trouble, telling me that I should never say anything about it.

‘But that was a long time ago!

‘In my opinion the treasure-chamber must be located under the curé’s château.

‘The tunnel which runs there exits under the sacristy and the Devil in the middle of the chapel’ (?) [Footnote: This statement is certainly false. The ‘Devil’ is the font supported by a devil which is located inside the church, on the left-hand side as one enters. The sacristy is a long way from there.]

Should we really take this strange story seriously?

We are very sceptical since Pierre Alquier, who is used to sleeping under the stars is certainly capable of making up a story if you buy him a drink!

What is more, if he was born in 1908 as he claims then he was only 8 years old when Saunière employed him as a navvy, which is hard to believe!

Whatever the case may be, the treasure has existed and it certainly still exists, as the following extract from a letter taken from Monsieur Corbu’s files and written to Saunière by one of the curé’s friends seems to suggest:

‘You cannot say anything publicly, but if you confess then you will be absolved because you have nothing to reproach yourself for.’

Alas! Saunière never wanted to confess anything about the treasure to anybody except to his mistress, Marie Denarnaud.

And yet the secret is not impenetrable.

A resident of Rennes-le-Château who perhaps knows a lot about the subject said one day to a member of the Club des Chercheurs de Trésors:

‘The secret of the billionaire curé lies at the bottom of a tomb – it’s just a question of finding out which one...’

One day therefore the billions hidden by the old curé will perhaps be found by the gravedigger, and then it will be so much the worse for the little village perched on its rocky eminence, for it will lose the most obvious part of its mystery – or the most obscure part of it, whichever you prefer! [Footnote: In 1965 Noël Corbu sold his restaurant in Rennes-le-Château to launch a hotel-chain and a factory. He couldn’t have done more to make everyone believe that he had found the treasure! But we prefer to think that, after 12 years of searching in vain, he has decided that it makes sense to abandon the arid hills of the Corbières and their deceptive treasures!]

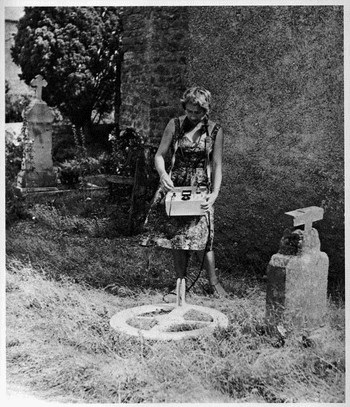

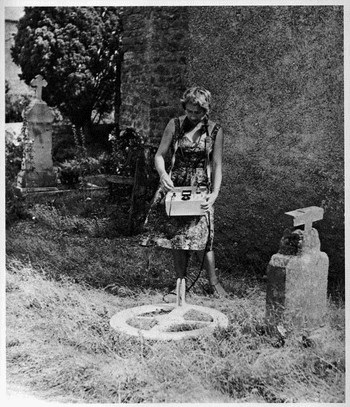

The treasure is thought to be hidden in the cemetery. Many points give off a signal but a permit is required to open a tomb (photo credit: Robert Charroux).

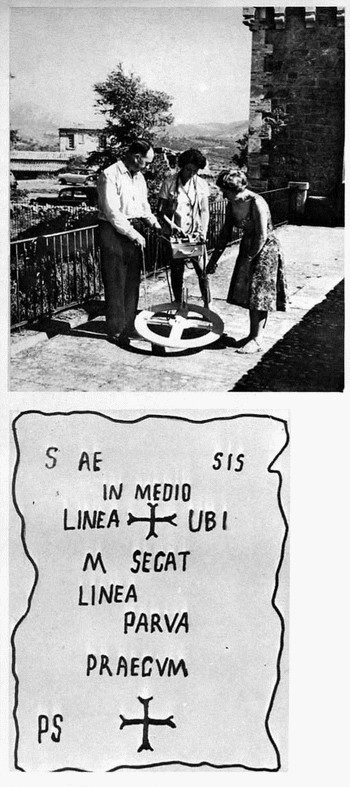

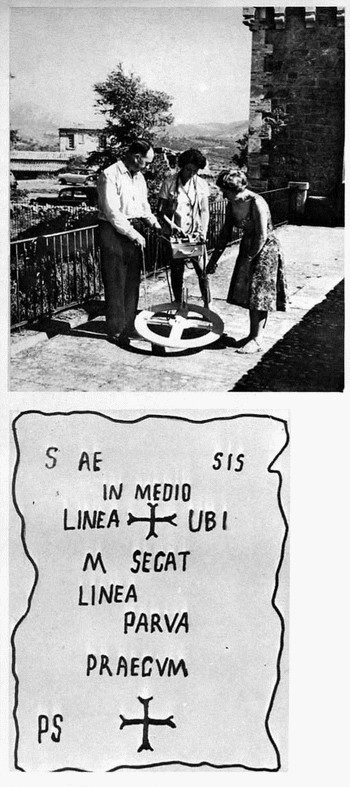

Upper – Noël Corbu, Denise Cervenne and Yvette Charroux detecting on the rampart-walk of the château.

Lower – Reconstruction of the drawing of the Stone of Coumesourde (photo credit: Catherine Krikorian)

* * *

|